Skip to content

#1 Ind vs Pak - April 18, 1986

#1 Ind vs Pak - April 18, 1986

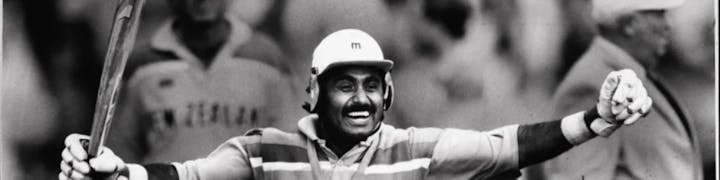

Pakistan needed four runs to win the match off the last ball, Javed Miandad hit a six of Chetan Sharma to win.

The power of a six

Where were you when it happened?

On April 18, 1986 - a hot day in Sharjah - Miandad batted out of his skin to win Pakistan the Austral-Asia Cup. It was a match that Pakistan was losing right until Miandad smashed a full toss from Chetan Sharma out of the ground from the last ball. . In that instant two competing emotions took hold. Pakistan realised that they could become a team of achievers; India developed a neurosis, worrying that if they could not beat Pakistan after such domination, when could they beat them?

Since that time many players, commentators, and fans have wondered about the effect of that one strike on the psyche of the two nations. Did it give Pakistan an unimaginable boost? Did India suffer a crushing, morale-sapping blow? If so, how long did this effect linger?

It took 20 years for India to have its magic moment. Sachin Tendulkar's upper cut six off Shoaib Akhtar in the 2003 World Cup started another a domination that restored the Indian psyche.

South Asian cricket has been dubbed war minus the nuclear missiles. The result of a sports match can trigger cardiac deaths,

and contests between India and Pakistan have prompted shootings, riots, killings, and sudden death. Cricket has been used as an extension of foreign policy—to instigate peace or prolong hostilities. However, regional cooperation will probably increase prosperity, with some commentators arguing that cricket is an important component of public health strategies.Facing up to the future requires a dispassionate appraisal of the past. How have India and Pakistan fared against each other in cricket? To answer this question—uppermost in the minds of over a billion people in South Asia and many millions outside—we compared 50 years of test matches and one day matches between India and Pakistan. One incident galvanised the emotions of these two nations.

In 1986 Pakistan batsman Javed Miandad scored a dramatic match-winning six off the last ball in a one day match that his side had looked like losing until that delivery—a shot heard throughout South Asia and much of the world.

The mid-pitch conference lasted at least twenty seconds. , one hand on hip, one on bat, lush moustache dominating face, now remembers remarkably little of it. 'It was one of those nothing ones, where you just hang around, catch a breath,' he says. The conference the ball before had been, he believes, the crucial one. 'That was when I had told him that we have to take a single, no matter what.

'Him' remembers it differently, as perhaps he would. --no off-spinner so resembled Lionel Ritchie--wasn't even supposed to be there. The wicketkeeper Zulqernain had been sent above Tauseef, after Ramiz Raja told captain Imran Khan that he hit big sixes in club games in Lahore. He could, but he didn't--despite Tauseef telling him to go for a single to get Miandad on strike just before he went out--and when he was bowled attempting one of those sixes, two balls were left, five runs needed.

Tauseef's memory is sharper, and in it, he inverts what Miandad wrote in his autobiography. Perhaps his children believe him. 'I told Javed when I came out that we simply had to take a run no matter what, even if the ball went to the wicketkeeper. Javed asked me whether I was sure, and I said we don't have a chance otherwise.' So Tauseef bunted towards cover and ran. Mohammad Azharuddin, one of the world's best fielders, ran in, picked up and missed the stumps from no more than four feet.

Chetan Sharma bowled perhaps the world's best-known yorker gone wrong

Then came the mid-pitch conference. 'He came to me and asked me, "What do you think he'll try to do?''' continues Tauseef. 'I said he'll definitely go for a yorker. Javed said, "Yes, and that means it could also become a full toss if he doesn't get it right." In any case, Javed was standing out of his crease a little.'

Almost everyone in the Indian team came up to the pitch to discuss who should bowl the last over. We finally decided that Chetan's extra pace and swing would prevent the batsmen from getting the runs. Tauseef Ahmed walked in and I heard Javed telling him: 'Whatever happens, we have to run. Hit or miss ... just run.'

Chetan's plan was to bowl a yorker but it was a waist-high full-toss. None of us expected Javed to hit it out of the ground.

The entire over was chaotic. Javed kept swinging wildly, and Mohammad Azharuddin missed a simple run-out. On the second-last ball, Javed got an inside edge and Roger Binny pulled off a superb stop down at short fine leg.

After the mid-pitch chat, Miandad stood at his wicket looking around the field. He needed four somewhere. He counted fielders around the ground--perhaps hoping it had swallowed a few--and took guard. Had Miandad successfully petitioned God for the ideal delivery, he could not have conjured up a better one; a thigh-high full toss, swinging in to his legs. He put it somewhere in the region of the stands at midwicket, arms raised almost in one motion from finishing the shot, and off he ran. Iftikhar Ahmed, the TV commentator, waited three seconds before concluding: 'It's a six … and Pakistan have won … unbelievable win by Pakistan …'

Like cartoons running away from a building on fire, Miandad and Tauseef hurtled to the pavilion from where a sizeable crowd was already pouring out. Smartly, Miandad--just behind Tauseef--curved away off-screen, while Tauseef went straight into the fans. He was greeted by fast bowling teammate Zakir Khan just before a shurta, local police, seemed to knock him down with his baton, trying to control the crowd. 'No, no, he didn't hit me,' Tauseef busted one enduring comic myth, 'he just bumped into me and knocked me over.'

It was like a funeral in the Indian dressing room afterwards. Chetan was on the floor. None of us knew what to do for nearly an hour. Nobody looked at anyone; we all just sat with our chins down, thinking about the possibilities. We could hear the celebrations outside but it was extremely depressing inside.

Sharjah had become a hotbed of India-Pakistan rivalry, its stands crammed full of expats and its executive boxes jam-packed with celebrities. Television had begun to cast its mesmeric spell upon the people of South Asia, and the combatants were rising in stature on the world stage, flexing their pulling power.

Pakistan had never really won any tournament of significance, and even the imaginatively titled AustralAsia Cup looked beyond them as orchestrated a faltering run-chase. Even down to the last over, India were in command, Javed's battling century futile.

That one shot was like a mince grinder in reverse. Into that burst went every strand of the transformation Pakistan had undergone over the preceding decade and half; the emergence of a superstar core, the spread of the game, the growing power of the player, the administrative vision of Abdul Hafeez Kardar and Nur Khan, the birth of departmental cricket, the rise of TV, more money. On the other side came out one solid lump of a golden age, the most golden age, in fact, Pakistan has ever had.

This was a gift from God.'

To Miandad, describing the innings is dependent on his mood and bearing. Sometimes it is a simple gift from God. 'Let's take it from the start,' he begins, and he really does. 'I believe in Quran and its verses. I read it right? So I used to always pray to God that in my own field, help me do this one big feat that will always be remembered. This was my prayer. 'I saw there were bigger players before me, who weren't remembered. So I always prayed that I do something big. I used to tell myself, even if I die in the field, I don't care. It's like a soldier dying on duty. It is shahadat (martyrdom). That innings was like a gift to me. I didn't play cricket like that, ever. That match … it was like a film. When I dream, it was like a film whose story has been written and now the film is being made. You cannot imagine one of the best fielders, from a few yards away missing three stumps, that you went in such crisis, wickets are falling, you are saved from a run-out, one four is stopped in last over, last ball finish, where the match was and where it went. This is a gift. To describe it is impossible. This was a gift from God.'

Sometimes he takes recourse in rationality. 'When I started, we'd already lost a few wickets, so the plan was to bat till the end so that even if we lost, we did with some dignity. Gradually, I started taking chances. Mostly I took risks with the running, but I'd hit a boundary and then stop for a few overs, before trying it again. We got to the last 20 overs still needing 9 or 10 per over. That was when I started actively working it out in my head, what we needed every over, where to get it, who to work with. By the time the last ball was to be bowled, I had become a computer: I knew exactly what Chetan was going to do, so I stood well out of my crease. He tried a yorker but being that far out, it became a high-ish full toss and I just swung. As soon as I connected, I knew it was gone.'

Introduced to the subcontinent in the 1800s, by the 1920s it was commanding great popularity in colonial India. In 1932 India became a Test playing country and, five years after the partition of 1947, Pakistan followed suit. In a cheerless, gloomy existence towards the bottom end of health and economic indices, the two nations found joy in cricket. It is easy to see why. Cricket provided a global forum for Pakistan and India to demonstrate talent and spirit, and defeat more advanced nations, such as England and Australia. Naturally enough, it cast a spell on the masses, became the embodiment of national self esteem, and turned cricket players into icons and celebrities.

A sport followed and played with equally fervent passion on both sides of the border has the power to be an instrument of peace, but it can also backfire, often quite unpredictably. For either country, a cricket loss to the neighbour can play havoc with national morale. Ruling party officials in India have expressed concern that a poor cricket showing in Pakistan might cost them the national election. In Pakistan, after India snapped cricket ties in the wake of the Kargil incursion of 1999, the mood turned sombre and national frustration began to crescendo. It is a testimony to the hold of cricket on the subcontinent that it took the restoration of cricketing links in the form of the 2003-4 series in Pakistan for the peoples of both countries to be finally convinced that the thaw in relations was genuine.

India and Pakistan played a match in Karachi. A largely Pakistani crowd exceeding 30 000 cheered the Indian team on to the field with a deafening roar. In 1987 Pakistani president Zia ul Haq had seized the diplomatic initiative by turning up at an India-Pakistan test match in Jaipur. This time in Karachi it was Priyanka Gandhi, Congress Party hope and heir-apparent to the Nehru dynasty, who made a splash that won her instant celebrity in Pakistan and may have wrong-footed India's ruling BJP. Even Colin Powell became a believer. “It's fascinating what sports can do,” he was quoted as saying shortly afterwards.

Cricket cannot solve the conundrum of Kashmir. But it can bring both parties to the table

Want to print your doc?

This is not the way.

This is not the way.

Try clicking the ··· in the right corner or using a keyboard shortcut (

CtrlP

) instead.